One of the great enduring myths of Government Relations is that the person with the fanciest title makes the decision. Ministers are the final deciders. Deputy ministers execute. Policy Advisors analyze. The machine hums along in a perfect linear fashion.

Sure. And the Leafs win the Cup every year.

Anyone who has spent more than ten minutes in Ottawa knows better. In this town, the org chart isn’t a roadmap. It’s a distraction.

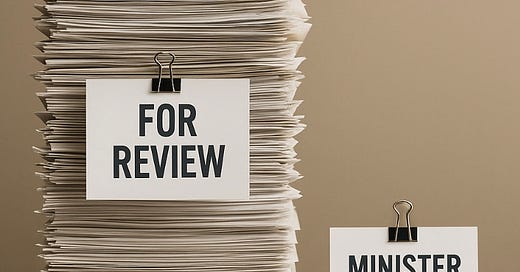

Want to know why your file stalled? Why that meeting with the Assistant Deputy Minister felt promising but nothing ever came of it? Why your shovel-ready project is still buried under six feet of silence?

Simple. You were talking to the wrong people. Or talking at the wrong time. Or, most likely, talking to people who looked like decision-makers but were not.

Here’s how it actually works.

Influence in government is like Nova Scotian weather in July. It shifts constantly. One moment it's clear skies and calm seas. The next, fog, wind, and sideways rain. The person with influence today might be out of the loop tomorrow. Someone who seemed peripheral this morning might be central by the afternoon. If you are not tuned in, you will be pitching your big idea in the middle of a downpour without an umbrella.

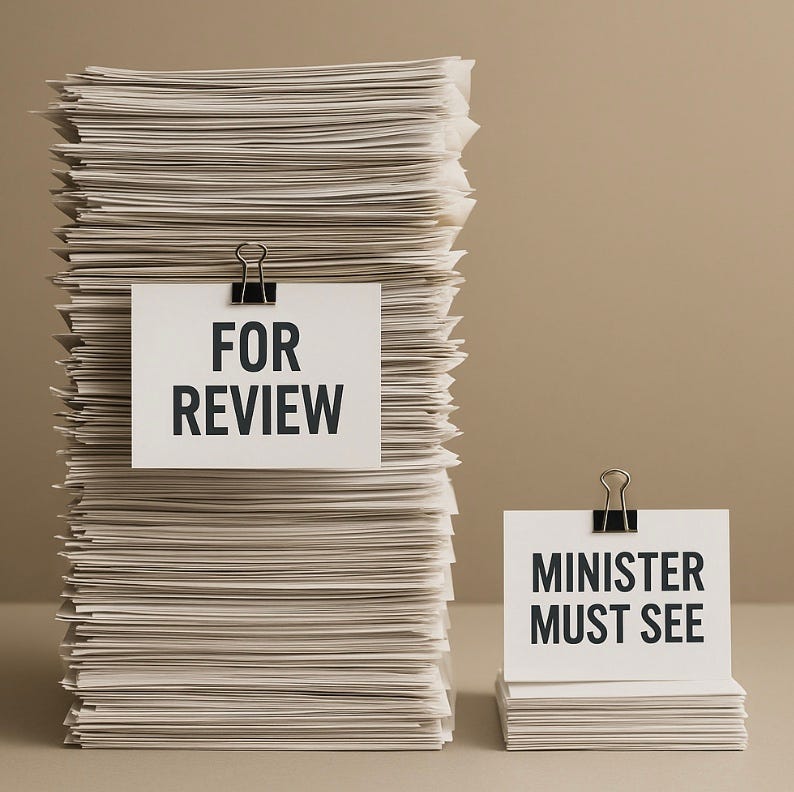

You can walk into an office and meet someone whose business card says Policy Advisor. Seems junior, so you ignore them. But that so-called “nobody” might have the Minister’s ear, write their speaking notes, and decide which ideas live or die before they ever reach the Minister’s desk.

Meanwhile, you are chasing a meeting with the Deputy Minister, who has not read a full briefing note since 2007. Why would they? They are managing this week’s crisis, not dreaming up new initiatives. They will politely nod through your pitch while their ADM is texting the junior civil servant who actually works on the file to ask if it is radioactive.

And here is another thing. Even when the answer is yes, it’s never really yes. Not until the PMO policy shop has weighed in. Not until Treasury Board signs off. Not until Finance approves the funding.

So no, the Minister doesn’t run the show alone. Neither does the Deputy. Sometimes it is a Communications Director. Sometimes it is a Chief of Staff. Sometimes it is the 24-year-old political science grad from the riding who spends their weekends going to fundraisers with the Minister. More often than not, it’s some mix of all of them.

I remember one office I worked in where the Chief of Staff seemed like the most powerful person on the team. Big title. Good salary. But the real influence belonged to the Stakeholder Manager, the one who had worked with the Minister since she was a backbencher and who drove her to and from work daily.

That staffer had both the first word and the last word with the Minister. Every. Single. Day.

No job description could capture that kind of access. But in politics, access is power. And if you missed that dynamic, you would never understand why certain files flew through while others never left the tarmac.

This is not dysfunction. It’s how complex systems work.

It’s also why so many smart people get nowhere in Ottawa. They assume a system built on formal authority will behave rationally. But politics does not reward rank. It rewards relevance. And relevance, like the weather, never stays still for long.

To navigate that, you need more than a contact list. You need to know who actually moves files in a given office. Who gets looped in early. Who wants to solve problems, and who is just waiting to move on to their next job.

You also need timing. Propose a great idea the day after an election call? Too late. Pitch a pilot project the day before the budget drops? Good luck. Ask for money during a fiscal freeze? Tell your board to stay calm and carry on waiting.

But when you do find fit. When the policy is right, the politics are quiet, and the personalities align, you can move mountains.

It just will not happen the way you thought it would. It never does.

So stop chasing titles and start paying attention to how things actually get done. Talk to the people who know which way the wind is blowing. The ones who shape the briefings, control the calendar, or ride shotgun to the Minister. In Ottawa, the biggest mistake you can make is assuming power comes with a nameplate.

It doesn’t.